- Home

- Sue Hubbard

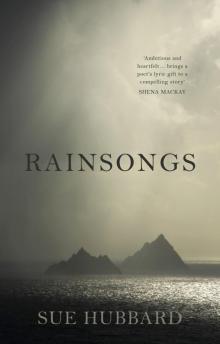

Rainsongs Page 8

Rainsongs Read online

Page 8

She’s getting maudlin. The lunchtime wine must be going to her head.

And you Eugene, what have you been doing since I was last here?

He lifts the bottle from its plastic cooler and pours her another glass. She doesn’t refuse. What the hell. There’s nothing else to do now that she’s stuck here with him except drink and listen.

He begins the long narrative about his divorce from Bridget, complaining that she’s ‘taken him to the cleaners’ and is still fighting for the Kinsale house. Why do all stories of marital failure follow the same script?

And your son? You’ve a young son haven’t you?

Rory? Yes, he’s mostly with his mother when he’s not away at school. This time it’s Eugene who looks away.

He’s not an easy boy, you know. Though I’m told that’s quite normal. Just how teenagers are these days. He comes to stay sometimes. Sits and plays computer games and loud music. I don’t see him much. We each do our own thing. He’s not interested in golf or shooting and I’m very busy. That’s partly why I wanted this chat, Martha, he says, relieved to be on what he seems to consider safer ground. I’ve a few plans up on Bolus Head. A spa. It’s going to be the best in Ireland. Very exclusive, I hope. And it’ll bring much needed work to the area, he adds, as if throwing a dog a bone. But it’s not straightforward. I own some of the land up there already, but not enough to make sure no one else can build or to guarantee the necessary rights of way and access. There’re a couple of small farmers up there. Some are only tenants and most of the others are happy to be bought out. But there’s one crucial place I need for the thing to go through and I think I’ll have a problem with that. And then, he adds slowly, there’s your field and without that and your man Paddy O’ Connell’s land the whole project will grind to a halt. I’ve got the fellows down in my office on the case. But it’s not easy, even for a property lawyer, he smiles wryly. But I’m hoping that you and I can come to a friendly arrangement. In your case it’s only the strip at the bottom of your field that connects to Paddy’s land. So you’ll not be missing it. By the way, I presume you don’t have any other plans for the place? Dessert? They do a very good sticky toffee pudding here. Or maybe an Irish coffee?

She can’t bear to listen to him. There is something lost about him. A man, who despite his millions, has no idea what’s important. She thinks of his son, Rory, sitting in front of endless computer games, instead of playing cricket with his father on the beach. Of Paddy O’Connell up in the high fields in the early mist, his Wellingtons caked with mud, content with his own company. He is the last vestige of an old Ireland, connected to land and cattle, Church and family. For earlier generations there was much less emphasis on personal fulfilment. Marriage, yes, and producing children. But after that you just got on with it. Making a living, caring for a family and stock left little time for the subtleties of personal growth. The Church set down the rules. Relationships with husbands and wives, children and neighbours may, at times, have been strained but Belief provided the framework. People like Paddy O’Connell, the monks and lighthouse keepers, defied the modern assumption that material advancement and emotional intimacy were essential to happiness. That not to have these things was to be deficient. When she sees Paddy carrying hay up to his cows, dressed in his neat overalls, his eyes reflecting back the colour of the sea, he doesn’t seem like a disappointed man to her.

At Eugene’s party all people talked about were property prices. From one of the poorest and most backward countries in Europe, Ireland is now one of the richest. Its current legacy not new poets or story tellers but a blight of vulgar bungalows scarring this dramatic landscape.

I don’t know yet, Eugene, what I’m going to do. I’ve only been here a couple of days. It’s too soon to decide, she says.

They finish the Chablis, making small talk and he pays the bill, then drives her back to the cottage. They don’t speak much. Then, just as she’s opening the car door he leans forward, his mouth, with its wine-soaked breath, brushing not just her cheek but her lips. She pulls back. Pats him maternally on the arm, then manoeuvres herself out of the car.

I’ll pretend you didn’t do that.

2

Cable O’Leary’s is packed. Girls in short jogging tops, white midriffs exposed above skinny jeans, stand around drinking Bacardi and Cokes. Middle-aged men, the belts of their stonewashed jeans pulled tight over ample stomachs, talk loudly above the music, while their wives sip sweet white wine, laugh and mostly ignore them. A Guinness toucan and row of little plastic harps nestle on the shelf above the bar among the Baileys and the Jameson. Martha takes her glass of wine and manages to find a free seat by the Ladies. It’s a moment or two before she realises that the fiddler on the small stage is Colm. There’s also a bearded man playing a flute whom, she presumes, must be Niall. And a girl with spiky red hair accompanying them on a bodhran.

Now this next song, the bearded man announces coming to the front of the stage, is written by my friend, Colm here, he says nodding in his direction. He’s a poet but too much of a shy eejit to introduce it himself.

The bodhran and flute begin slowly, counterpointed by Colm’s husky voice. There’s something timeless about it that captures the spirit of this harsh place. The history of the megalithic stones scattered over the headland. The collapsed walls and abandoned dwellings where the occupants were forced to leave, after another failed crop, for the tin mines of Colorado or a sheep farm in New South Wales. When the set finishes the musicians down their instruments and gather at the bar. They seem more ordinary than on stage. Just three young people having a drink and a good time. She wonders, as they collect up their pints and head outside for a smoke, if either Colm or Niall is the boyfriend of the girl with the spiky hair. She imagines them climbing into his battered VW van. Taking off to gigs in Waterville, Caherdaniel or Portmagee. Bedding down in the back in their sleeping bags in a fug of Guinness and roll-ups after another late night session, before taking to the road again. Above the bar the poster says their band is called Caidre.

Apparently it means friendship.

She gets up and goes to the Ladies. When she returns to order another glass of wine, Colm is sitting on a high stool at the bar with his back towards her, talking animatedly to his friends. He’s wearing a scruffy leather jacket and his ubiquitous blue woollen hat. As she waits to be served someone calls his name. He turns and notices her. Smiles. His teeth are slightly snagged like those of a ten year old in need of a brace.

Hey Shane, get your arse down this end. There’s a lady waiting. Did you hear the set, Martha? Can I get you a drink now?

She can’t remember telling him her name.

3

The Tate or the Courtauld might want Brendan’s papers if they are collated and catalogued. She’s trying to save what she can. But the more she reads, the more the Brendan she knew, the man who put on his white towelling robe each morning to go down and put the Italian percolator on the hob for his first espresso, the man who when she returned home tired after a hard day in school, opened a bottle of Pinot Grigio and laid out a dish of olives to signal the end of their time apart, seems to fade. To relive the past we start with a few known facts. Then add texture and colour, so that like a child’s dot-to-dot drawing we arrive, if we’re lucky, at an approximate outline. Though often it’s not quite what we expect.

It was a freezing November day for Brendan’s funeral. She was surprised by the turn out. Nick Serota from the Tate. Norman Rosenthal, Anthony and Sheila Caro, Sean Scully. Collectors, curators and artists that Brendan had known over the years. Some well-heeled. Others down on their luck, happy enough for an egg and cress sandwich, a cup of tea or a glass of sherry after the service. She remembers the cloying fragrance of lilies. The sea of sombre coats as she stood under a dripping umbrella, receiving those who wanted a word with her in the porch of the crematorium. At the reception a young waitress in a very short black dress served vol

-au-vents from a silver salver. Brendan would have enjoyed that.

She was poised and calm but inside felt, what? Angry and abandoned. She got through it all like an automaton, as if giving a performance. There was a strange euphoria, a sense of drama at the heightened emotion of it all. Then the grey loneliness descended permeating everything. The books that sat unread in Brendan’s study. His paisley dressing gown hanging limply on the back of the bedroom door. His shaving things that lay neglected in the bathroom, which took her weeks to chuck out. As if by throwing them away she was being disloyal. It was there in the footsteps of strangers echoing along the hard city pavements in the early evening. In the casual banter of drinkers spilling from Islington pubs at closing time. The couples snuggled inside each other’s coats as they waited in the rain for the night bus to take them home to their shared beds. It filled the visible day and her solitary nights, reminding her that she was quite alone.

Wednesday

1

Paddy O’Connell lies in his narrow bed listening to the storm. Such nights are as familiar to him as the beating of his own heart. It’s why he lives here. To be close to the wind and the sea. To watch the first light creeping across Bolus Head. This is the time he likes best when he feels as if he’s the only man in the world. Yesterday he saw that Cassidy woman, Brendan’s widow, out walking. That was a sorry business. A heart attack and Brendan still a young man. Pretty much the same age as himself. Brendan came here to write his books. He always seemed very English but his grandfather was from these parts. She looked a bit lost trailing up the track in her bright-green anorak. He hasn’t seen her for years. Not since that summer. She’s still a nice looking woman. Younger than Brendan. But until now she’s never been back. He can’t really blame her in the circumstances. When they met on the track she stopped to pass the time of day and ask if she could go across his field down to the black rocks to get a better view of the Skelligs.

No reason why not, he said, if she minded how she went. It was easy to slip.

I’ll be careful, she smiled. You know you must live in the most beautiful place in the world.

He couldn’t really disagree with that.

2

Before it’s light he puts the kettle on the hob. He’ll take a quick cup before going out to see to the animals. Get the warmth of it in him. While he waits for it to boil he pulls on his overalls, finds a box of matches and lights the stove, then pads in his thick socks to the little bathroom off the kitchen to shave. Swishing the lather in the soap pot with his shaving brush, he works it into a foam on his cheeks. With his head cocked under the neon glare he scrapes it off in front of the medicine cabinet mirror with his new disposable razor. Splashing his face with cold water he pats it dry with the striped towel hanging on the back of the door, then takes the tortoiseshell comb from its blue plastic mug. It’s the same comb he’s used since he was a boy. And he uses it to tame his mop of grey hair, flattening it with a lick of water. He remembers his first communion. How he plastered down every hair on his head with a film of Brylcreem. They rehearsed for weeks the difference between mortal and venial sins. It was confusing for a seven-year-old. Being disobedient to his parents or teachers was certainly a sin, but what about breaking a plate or forgetting to bring in the turf? His mother took him over in the donkey cart. There wasn’t much of a fuss. Just a cup of tea and a sugar bun with pink icing after in the priest’s house next to the church, with all that dark furniture and the pictures of the crucified Christ with his crown of thorns and wounds in his side. His sad hurt face. There were red velvet curtains hanging at the windows, the like of which he’d never seen, and a rug with swirling patterns in front of the hearth. He can still remember the smell of Jeyes fluid and mothballs. The priest’s housekeeper brought tea on a tray and put it on the table in the window on top of the crocheted cloth. There was a separate jug for the milk and a china bowl with silver tongs for the sugar. He sat in silence as the priest poured and handed a cup to him and one to his mother, who was perched uncomfortably on the edge of a padded velvet chair in her Sunday coat and the hat and the gloves she kept especially for funerals and weddings. Despite the pink sugar bun, Paddy couldn’t wait to leave.

But when it came to his confirmation it had been more complicated. You could be kept back if you didn’t know the right prayer. Some of the less bright kiddies struggled or got nerves. They could already be long gone out working and still not confirmed. The Bishop of Kerry was a tall man then. When he put on his mitre he stood near seven foot high. They were all examined in advance and then asked a question. His was ‘what are the fours signs of the true Church?’ He doubts many would know the answer today. You were given a card and without that precious card you’d be making no confirmation. Be put back till the next time. And as the confirmation was only every three years, you might have a bit of a wait. It was short pants he wore, then. And a new shop-bought jersey. For a while he wondered whether he might have a vocation. But football was his passion. Playing with the other lads up in what they called the Flat Field.

And he liked to listen to his da. About the time before he was born and the Economic War, when exports from Ireland were heavily taxed going into Britain, so prices were low. He’s just too young to remember the night a fleet of bombers passed over Caherciveen on their way back to Germany after a raid on the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast. It was a moonlit Sunday night. Jamesy O’Sullivan from down the hill was over for a visit. He and his da were taking a pipe of tobacco when there was this tremendous roar along the coast and the house shook with the vibration. He’d never heard the like in all his days, his da said.

He’s not much of a one for politics but Paddy remembers the stories of the bad old days. How the Black and Tans threatened to burn down part of the town. How everyone waited on their arrival, though most of the women and children left to find safer places, dispersing out on the moor, in sheep shelters and ditches. Some even ventured up the mountain. But, thank God, they never came. Not that night anyway, only getting as far as Maggie Sheehan’s place.

This, then, is his life. It’s mostly always been his life except for the time he was away in Dublin. Three generations. His grandfather farmed here. A small man of great physical strength, he built the stone walls with his own hands, digging the boulders from the ground with a spade and moving them in a hand-barrow. It was slow, backbreaking work. A lifelong smoker he always took a sod from the hearth when he left for work. In the absence of matches it was a necessity for a man addicted to his pipe. But the tobacco got him in the end. He was confined to his bed for months before he died. Paddy can still remember his da bringing the lifeless body downstairs wrapped in a blanket, with the help of a neighbour. It was the first time he’d seen a dead person. His grandfather was laid out on the bed, just off the kitchen, under the statue of the Virgin. Then shaved with a cut-throat razor and dressed in the brown habit especially purchased for the purpose years before and periodically hung outside for a good airing so it didn’t get the moth. All the clocks were stopped and the mirrors turned. Two new white candles were lit and placed at his head. The clay pipes, tobacco and snuff laid on the scrubbed table. Every male caller was expected to take a puff to keep the evil spirits away.

Along with his elder brother Mikey and his younger sisters Bridie and Marie, Paddy was charged to sit with the remains. Nora was making cups of tea and cutting thick ham sandwiches with his mam in the kitchen. The weather was warm and they were to make sure the flies didn’t lay eggs on his granda’s face. In the small, poorly ventilated room these could hatch out quickly and cause embarrassment. They sat with their eyes peeled, relishing the seriousness of their task, swatting any insects that dared enter the room with a folded newspaper. The window was kept open and they were instructed to be careful not to stand in front of it in case they prevented their granda’s soul from leaving. After two hours, when no one was looking, Mikey got up and shut it, just to make sure that his soul didn’t fly

back in again.

Friends and neighbours took it in turns to sit with the body through the night and recite the rosary. Paddy was scared of the coiners, the professional mourners in their black shawls. All the women joined in the keening, wailing and carrying on. But there were also games. ‘Priest of the Parish’. ‘Riddle-me-Ree’. And Tommy O’Flaherty from down the way dropped by with his fiddle. No doubt a stranger, unaccustomed to their ways, would have looked on all this merriment as irreverent but when he was a lad, it was an accepted part of the wake. All the next day people called to pay their respects and talk about his granda. After prayers everyone, except those sitting up all night with the body, dispersed and supper was served beneath the flickering oil lamps. Soda bread, baked ham, pies and cheese, with whiskey for the men who stayed drinking in the kitchen, while the women went to the corpse room. The following morning Paddy had to dress in his Sunday clothes and polish his boots. Then, just before the funeral procession left, the open coffin was lifted onto two chairs and he and his siblings were instructed to line up and kiss their granda goodbye. He was shocked by how small and shrunken he seemed. His cheeks had collapsed, his nose become beaky and his thin hands poked from his long sleeves like the claws of a malevolent bird. After the lid was nailed down and the coffin put onto the donkey cart, the little procession followed behind on foot, twisting down the mountain to the churchyard in the rain.

They were a big family. Between the eldest and youngest there were fifteen years. Brothers and sisters arrived regular as clockwork. The midwife usually came before the doctor and would shoo all the children upstairs. Paddy can still remember the commotion as they huddled under the faded paisley eiderdown on the big bed in the back bedroom with their sugar sandwiches, trying to make sense of the unfolding drama downstairs that signalled the new arrival. But where it had come from was anyone’s guess. For all he knew it had come down the chimney like Santy. The previous night it wasn’t there and now it was going to be part of the family. How innocent they were. But that’s how it was then. No TV, no radio. And no way of acquiring any information, except from parents, teachers or the priest. And none of them were forthcoming. Even though he saw sheep and cows mating he never put two and two together. Nothing was ever explained. It was only after he watched his first calves being born that he began to work things out. One night he followed the yellow circle of torch light to the barn and stood among the rain-wet straw as his da approached the lowing cow. He can still remember the rain drumming on the tin roof, the puddles in the yard. He couldn’t take his eyes off the calf hanging, half-born, from the red-gash between her back legs. The umbilical cord round its neck, its tongue lolling and frothed with white. His da rolled up his sleeves and slipped his arm up to the elbow inside the dark cavity to unhook the tangled feet and legs. Then something gave and the calf slipped out wet and shining. He felt sick at the sight of the bloodied puddle of jelly that followed but stood transfixed as the exhausted heifer licked her glistening calf to its knees and it began to nuzzle at her teats.

Rainsongs

Rainsongs