- Home

- Sue Hubbard

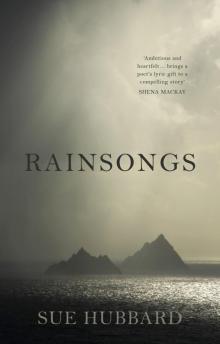

Rainsongs

Rainsongs Read online

Praise for Previous Books by Sue Hubbard

‘[Hubbard] has the precision, the respect for words and pain, of a poet’

John Berger

‘Beautifully written and wholly knowledgeable… a triumph of literary and artistic understanding, a tour de force: masterly, moving… you are the less for not reading it’

Fay Weldon

‘Lyrical, highly visual and beautifully observed’

John Burnside

‘Haunting, sensuous and at times disturbingly sharp… [Hubbard’s] eye – and her touch – are vividly alive to pleasures of surface, as well as to dark depths of anger and melancholy’

Marina Warner

‘Generously of life and warmth and technical mastery’

Sebastian Barker

‘A writer of genuine talent’

Elaine Feinstein

‘Dazzling’

Ruth Fainlight

‘Her descriptive powers are peerless’

Metro

Also by Sue Hubbard

FICTION

Depth of Field

Rothko’s Red short stories

Girl in White

POETRY

Everything Begins with the Skin collection

Twenty poems included in Oxford Poets

Ghost Station collection

The Idea of Islands poems with drawings by Donald Teskey

The Forgetting and Remembering of Air Collection

ART

Adventures in Art Selected writings from 1990-2010

Rainsongs

Sue Hubbard

Author Biography

Sue Hubbard is an art critic, novelist and poet who has contributed regularly to a wide range of publications including the New Statesman and The Independent, and has also written for The Sunday Times and Observer. She has contributed to many arts programmes, including Kaleidoscope and Night Waves.

Twice winner of the London Writers’ Award, her poems have been read on BBC Radio 3 and Radio 4 and she is well known for her poem Eurydice – London’s largest public art poem – which stretches across Waterloo station, made possible by a grant from BFI and The Art’s Council. Rainsongs is her third novel.

In memory of my parents

‘Yes, of course, if it’s fine tomorrow,’ said Mrs Ramsay. ‘But you’ll have to be up with the lark.’

Virginia Woolf, To The Lighthouse

‘What’s past help, should be past grief,’

William Shakespeare, A Winter’s Tale

Is beag an rud is buaine ná an duine:

The smallest of things outlives the human being.

Irish Proverb

Kerry, AD 520

Twelve men dip their oars in the waves. The sails of their curragh are full. The rowlocks slick. Ten young alders have been felled for timber and eight oxen hides soaked for days in ash-filled water. The yellow fat scraped off with knives, then dressed with sheep tallow and polished smooth with round stones. Wet wood creaks against leather. Yet despite setting out on the feast of Lughnasadh when all is ripe and benign on the land, the weather has turned. The swell is as high as a man. Their woollen cassocks are drenched. Their hands blistered with salt. In the stern the priest prays to spare the boat and save the men. As the narrow vessel plunges through the surf, they sing.

For months they have copied Sacred Gospels onto calfskin and vellum with goose quills using red ochre and green verdigris, yellow orpiment and blue from honey-smelling woad. These are the Holy texts they will live by. When they left the mainland the whole community crowded into the little church for the blessing. After the Mass their brothers filled rush baskets with soda bread and fresh-churned butter. Honey from their hives. Wrapped bees-wax candles and clods of turf in dry sacking, filled tar-stopped pitchers with new-brewed ale. Goat skins with sweet water.

The sea is their desert. None knows if this journey will end in his death or deliverance. These things are not in their hands. Ahead there is nothing but the bone-chilling ocean and, if they are blessed, the face of God. Now they must endure as He endured. May the good Lord keep them safe. Nearly there. Nearly there…

Domine, dirige nos.

Saturday 29th December 2007

1

Brendan is dead. There, she’s said it. Out loud, in the empty car. Unlike his lifeless body lying in the floral hospital gown, his face pallid against the dark growth of stubble, the words make it fact. I’m sorry, the weary young doctor said just past midnight. But she hadn’t believed him. Coming here forces her to accept her loss. This was always his place. She’d been here with him, of course, but not for a long time. Not since that summer. She’s not sure whether she’s come back to reclaim or to exorcise him. She grips the steering wheel tighter and the windscreen wipers click backwards and forwards like demented woodpeckers. It’s very dark outside. On the brow of a hill she stops at the crossroads to check the map but the roads don’t correspond with those on the page and there are no signposts. The locals know where they are. Ahead there’s nothing but more rain and four small squares of light twinkling across the glen. Hadn’t suicides once been buried at crossroads so the shape of the cross would protect the living from their restless souls? Had that been true here, too, she wonders, given that suicide was a mortal sin in the eyes of the Catholic Church?

In the distance a dog is barking.

She’s been going round in circles and twice found herself heading back on the road towards Caherciveen. Squat bungalows, strung along the road, flicker beneath rain-flecked Christmas lights. A Santa plunges in his sleigh across a roof. A blue star flashes above a porch. Illuminations more suited to the end of a pier in a tawdry seaside town than a remote village on the west coast of Ireland. A few miles back she’d got stuck behind a caravan of cars and couldn’t work out why there was such a traffic jam in the middle of nowhere on a wet winter’s evening. Then she saw them coming out of the pub: the old men in flat tweed caps, a cigarette stub glowing between cupped thumb and forefinger, women in good black coats and gold earrings, girls holding down their short skirts against the boisterous wind. Aunts and uncles, sisters and cousins once removed. Huddled under umbrellas, their clouded breath evaporating in the cold wet air, they chatted before climbing into old vans, BMWs and 4x4s to leave the wake and return, down lanes fringed with barbed wire and deep ditches, home.

The windscreen wipers continue to tick, smearing the beads of rain on the muddy glass when, suddenly, something darts in front of the headlights and she brakes. A small white ferret stops in the middle of the road, stands on its hind legs and sniffs the air. It has bright red eyes and a rat in its mouth. She rubs the misted windscreen with the sleeve of her anorak and winds down the window. A blast of cold air, thick with the stench of fertiliser, hits her in the face. If she concentrates hard enough she might hear the sea. But the only sound is the rain drumming on the car roof. She has no option but to drive on and hope that she remembers the way. There’s no one to ask. They’ll all be in the pub or watching TV in their new bungalows, a pair of concrete lions guarding the front gate.

And what will she do now that she’s here? There’s so much to sort out. Brendan came to write. For the rest of the time he let the cottage to friends: artists or academics who needed some peace and quiet. To the few in London who’d enquired, she said she was coming over to Kerry to sort out his affairs. And the truth? Well, she’s not sure. Maybe she’s simply come back to make sense of all that she was unable to attend to during those thirty odd years, with their brief joys and substantial griefs that turned out to be their lives. And now, here she is, a woman in her mid-50s, driving alone along a rain-swept Irish road

at the year’s end because she has nothing else to do, and nowhere in particular to go. And because, like everyone else on this earth, she has to be somewhere.

She winds down the window, turns on the heater and sets off again through the driving rain, down the narrow lane, turning up the volume of the piano concerto on Lyric FM. The music fills the car as if she’s in a cocoon. Separate from, yet somehow fused with the wet landscape outside. Part of her just wants to go on driving, to keep following the road wherever it leads. To become like an itinerant tinker, hanging her washing on a hawthorn bush. There’s something reassuring about not choosing a destination, not having to arrive and make decisions. After another three or four miles she comes to a green phone box and turns sharp left. A patchwork of dry stone walls criss-crosses the bare hill and a bone-faced moon hangs over the headland. Two shaggy ponies stand head to tail by a blackthorn hedge. At the end of the track she stops the car, climbs out, and opens the gate. She’s forgotten to bring a torch but the moon is bright enough for her to find the door. It’s stopped raining. The sky has cleared. Below the steep cliff the surf pounds against the rocks and above the sky is embroidered with stars. She recognises the Plough but not the other constellations. Brendan would have known. She thinks of that trip to the planetarium. Sitting tipped in the reclining seats between him and Bruno, as if swimming through stars.

Apart from the wind and waves, it’s completely quiet. The sea dark as tar and the white crests rolling into the far distance like streaks of light on a negative. This is the end of the world with nothing between her and America except the cold sea. She thinks of those medieval maps in the Vatican that she and Brendan saw in Rome. The known world was so much smaller then and at each parchment corner there’d lurked a monster warning of unimaginable dangers.

She pulls up the hood of her anorak and stands in the wind listening to the breakers. Rome. It had been a reconciliation of sorts. Brendan’s book had just come out. A reappraisal of the St Ives group and its importance to Modernism. Nicholson, Hepworth and Gabo, along with the next generation of painters: Patrick Heron, Roger Hilton and Peter Lanyon. Brendan had argued that, in their own indomitable English way, they were just as significant to the development of Abstract Expressionism as those working in their New York lofts. Just as radical as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. It took five years and was accompanied by an exhibition at the Hayward. A brave show in a climate more sympathetic to clever videos than to painting rooted in landscape and place. But it got good reviews. And it gave him a lift, a sense of purpose that she envied. He came here for weeks at a time to work on it, valuing the reclusive quiet. With its publication there were invitations to give talks at the Tate and the ICA. To contribute to the odd radio programme. Even before their lives were blown off course he never enjoyed simply being a gallerist. He relished the research, organising loans and tracking down hard-to-locate paintings, sniffing them out from obscure collections like some sort of arty Inspector Poirot. Work was his refuge. He travelled its highways and byways like an excited visitor to another country—leaving her abandoned at the border—creating an alternative reality, in ways that she was unable to do with her GCSE lesson plans and marking. Sometimes it made her angry. When he was working in his study at the top of the house in Myddleton Square, surrounded by catalogues and monographs, she longed to barge in. To ask what right he had to bury himself in all that art, all that stuff, to forget and move on. If she was going to be left clinging to the wreckage, then why shouldn’t he? But of course she never did. And, probably, he never knew how she felt.

She’s getting cold and feels for the key under the eaves. It’s still there on its rusty nail. She opens the door, finds the fuse box, and flips the switch. Everything is just as Brendan left it. The neatly stacked peat and kindling in the willow basket by the stove. The books on Caravaggio and Aboriginal art open on the little wooden stool standing at the end of the battered leather sofa spread with the paisley rug they’d found that first summer in a second-hand shop in Killarney. On the rough wooden shelves, erected years ago from planks balanced on bricks as if he was still a student, are his books on natural history and Celtic folklore, the complete works of Shakespeare and a monograph on Jack B Yeats. A half-drunk bottle of Jameson’s whiskey sits on the windowsill next to an arrangement of pebbles and driftwood, a collection of small animal skulls. In the alcove is an earthenware pot filled with stems of dried honesty. The room smells musty. As though filaments of white mycelium were already establishing themselves in the fabric of the building, penetrating the floor boards and rafters, the kitchen cupboards and drawers.

She goes to the wood basket and screws up a yellowing copy of The Irish Times, breaks off a fire lighter and places it inside the wigwam of kindling. It flares quickly, before dying back. Bending to blow the fragile flame, she creates a snowstorm of ash on the front of her anorak. Eventually the sparks catch the whiskery strands poking from the clods like the hairs from an old man’s ears. Though the place is legally hers she still feels like an intruder. She gets up and goes to the cupboard under the stairs. The light is broken, though she can just make out a brass coal scuttle, a cardboard box full of rope and assorted fishing tackle, a straw hat and some old pots of paint. There’s also a child’s bucket and spade. She shuts the cupboard quickly and goes into the kitchen to put on the kettle.

On the back of the door are Brendan’s battered felt hat, his muddy Burberry and a pair of binoculars in a tattered leather case. She’s never seen the binoculars before. As she slips her hand inside the jacket, she realises she has no real idea what her husband did when he came here. In the breast pocket she finds a postcard of the Skelligs photographed at sunset. Its edges foxed and curled with damp.

This chapter has been a bugger. Worked all day then walked down to Cable O’Leary’s for a couple of Guinness. Yesterday Eugene came over and whisked me off for a round of golf at his new place near Tralee. That man has the Midas touch. Hope your horrors are behaving and that Titania is proving a bit more co-operative and Bottom has stopped sulking. Don’t forget to take the car in for service. The clutch won’t last much longer. See you Tuesday week.

Brendan x

She stares at the familiar hand, taken aback by this prosaic message from the dead. There isn’t a stamp on the card. Perhaps he’d forgotten to post it or thought better than to send her a picture of the Skelligs. She slips it back in the jacket and goes in search of some matches and puts the aluminium kettle on the stove. There still isn’t an electric one. Brendan enjoyed the Boy Scout aspect of making do up here, of hauling in the fuel and the inconvenience of getting down to the shop. When he inherited the place there was no electricity. The first time they came they used Tilley lamps. Then it had seemed romantic. She searches the kitchen cupboards and finds a jar of mouldy Nescafé, an empty packet of Italian coffee and, in the blue and white striped jar marked TEA, some stale Earl Grey tea bags. She should have stocked up properly before she came but apart from a packet of dried pasta, some tins of tomatoes and sardines, a couple of onions and a box of eggs that she’d found in the cupboard at home and shoved in the boot of the car, she hadn’t planned any of this.

She’ll have to make up the bed but is too exhausted. She throws another turf in the stove, then pulls a pillow and an Aertex blanket from the pine ottoman and huddles on the sofa in her clothes to watch the glow. This will have to do. She’s too tired to do anything else. Anyway, she’s not sure she wants to sleep upstairs alone. She turns off the table lamp and tugs the fusty covers under her chin. A full moon floods through the small window casting shadows on the whitewashed walls. Yet despite the fire, she can’t get warm. The damp seeps into her bones. Lying shivering in the dark, she feels guilty that she let Brendan come back here alone. But that’s what he wanted and she was never able to face it. She wonders if he ever came with Sophie? She’s glad she doesn’t know.

Sophie Bawden had siren eyes. Perhaps if Martha had been a middle-aged man

in the midst of a crisis she, too, might have been lured by their sea-green depths. Cliché had matched fact. Twenty years younger than Brendan, Sophie was his editor at Thames & Hudson. Young and ambitious, she’d made a bit of a name for herself with her books on women surrealists. At the height of their affair Martha knew that Brendan had considered jettisoning their marriage and setting up home with Sophie. But somehow, someone—she wasn’t sure which of them it was had come to their senses, if sense it was—and Brendan had come back to her, held, no doubt, by something deeper than lust. She knew things were over between him and Sophie when he asked her to join him in Rome. It was as close to an apology as she was likely to get. So she accepted.

Each of them had dealt with grief in a different way. But it isolated rather than drew them close. She couldn’t remember how she got through that time. How she coped with his late homecomings, his furtive phone calls, the distance and evasion. Looking back she was, she realises, slightly unhinged. What hurt was that he barely bothered to cover things up. Though he never crowed. It was simply that after all their years together, after all they’d been through, they were leading parallel but disconnected lives. He stayed up late working and made a point of getting up before her or taking a shower after he came home, when he always bathed in the mornings. They never had words. Brendan took out his frustration straightening pictures, switching off unnecessary lights and going round the house turning down the heating. Neither spoke of what was really going on, lurching from day to day in a miasma of denial and indecision. She got through her classes as best she could, hardly remembering at the end of the day what she’d done with her lower sixth. It was as if to have discussed what was happening would unleash some great Leviathan that would have capsized them both. Much of the time she’d no idea who this man was who lived in the same house; flossing his teeth, putting out the kitchen rubbish and sleeping on the other side of the bed. It was as if she was cohabiting with one of those wooden Russian dolls and that her real husband was lurking somewhere inside.

Rainsongs

Rainsongs