- Home

- Sue Hubbard

Rainsongs Page 7

Rainsongs Read online

Page 7

Before this schoolhouse the children had to steal what education they could in one of the hedge schools set up in response to the 18th century Penal Laws that stated: ‘no person of the popish religion shall publicly or in private houses teach, school, or instruct youth in learning within this realm...’ In dry ditches, beneath blackthorn hedges or in the nook in a stone wall, Gaelic brehons secretly taught Irish literature, music and poetry, arithmetic and a smattering of the classics. The erosion of their native language was as powerful as any gun in the suppression of small communities. It had happened in Wales and the Basque country, too. This sweeping away of the vernacular and, with it, the grammar of memories that defined who you were. Peasant families bartered a flitch of bacon or a pat of butter for a bit of learning in their native tongue.

How little she really knows about Irish history. Cromwell and William of Orange had, in school, always been yoked to the ‘the Irish problem’. She knows about the potato famine and the Easter Rising. Had read Yeats at university. Knew something of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. About Synge and Tyrone Guthrie and the Irish Americans such as Eugene O’Neill. But her knowledge is little more than a list of names: Maud Gonne, Lady Gregory, Joyce, Beckett, the Black and Tans, Michael Collins, de Valera, and Sinn Féin. She remembers Bill Clinton and John Major’s peace efforts north of the border. The absurdity of the BBC banning Gerry Adams’s voice and dubbing it with an actor. But it was the London bombings that really brought Irish politics home. She and Brendan were in bed when the bomb exploded at the Baltic Exchange. The blast carried for miles shaking the windows of their Islington house. And around Christmas time she’d always felt nervous in Oxford Street in case the IRA should take advantage of the seasonal crowds. Then there was that time when a load of Semtex was discovered just up the road, hidden in a reservoir in Stoke Newington. Life infiltrates even when one’s minding one’s own business.

But things move on. Truth is only ever partial. Every picture a distortion in some way or another. Facts not entirely what they seem. Since the attack on the Twin Towers, the IRA seems like ancient history. She remembers how Brendan phoned from the gallery to tell her to switch on the television. How she stood alone, transfixed in the middle of the sitting room watching the growing horror unfold, her gaze focused on a lone man tumbling like a deep sea diver through the New York morning sky. She imagined him having coffee and cornflakes earlier somewhere in Tribeca. Kissing his wife and child goodbye before catching the subway to work, with no notion that this would be his last day on earth.

She doesn’t know who owns the pink cottage. When it was a school it would have consisted of one room. The small children at one end learning by rote. The older ones practising their sums on slates at the other. And then, without meaning to, she remembers that day, a life time ago, when Bruno slipped his hand nervously from hers and ran in through the school gate to join the other children. How she stood with a lump in her throat, because she knew as she walked back to the car that something had changed. That he’d moved off into his own trajectory. That this was the beginning of his pulling away. She worried all morning that he’d forget to ask for the lavatory. Imagined him among the alphabet posters and number charts, the pictures of farm animals, negotiating his place in the world.

She sets off again up the hill, past the lichen-covered stone walls. There are no trees except for a spinney of pines planted as a windbreak above the squat bungalow where a white goose is screeching at a tethered dog.

7

The pages of the old photograph album are foxed and faded. Images peel from the transparent cellophane corners that hold them flimsily to the page between sheets of yellowing tissue paper. She remembers taking some of the snaps—the ones on the beach—on her old box Brownie. But those in Waterville? Who was holding the camera? It can’t have been Brendan because he’s standing beside her. Was it Bruno? Her memories are so unreliable. She stares at the photos as if her concentration might enable her to explain some elusive mystery. But they are phantoms. Mechanical ghosts.

They spent most of that summer down on the beach or taking trips in the car on the odd hazy day. But usually they woke to a blue sky and the bay still as a millpond. Then they trekked with their striped windbreak and rugs, their sun hats, bathing costumes and suntan lotion, down the lane lined with purple and scarlet fuchsia, along the gorse-edged path, to set up camp at the far end of the bay. Brendan took a small aluminium framed deckchair so he could sit and read. She can still see him in his old khaki shorts and battered denim hat, his legs white after a winter in the city, rubbed bald around the ankles from his socks. His feet self-conscious in their unfamiliar sandals, as if his toes didn’t quite belong to him. She lay on her towel soaking up the unexpected Irish sun, her head resting on her arms, squinting through her fingers to keep a watchful eye on the small figure leaping like a salmon through the waves.

Watch me. You’re not watching.

On the green towel beside her were his sand shoes. His T-shirt with the palm tree embroidered on the front, his checked shorts rolled into a ball. She looks out across the silver bay. And, for a moment, can feel his presence so keenly that she can smell the crusted salt on his skin. But that was another life. She was someone else then. She came here to wind up her husband’s affairs, little thinking how these other banished ghosts would surface to haunt her. If she’d considered it at all, she would never have come. It was here that she’d last felt wholly and unconsciously herself. She’s almost forgotten what that was like. Like an amputee she’s got used to her loss. Only occasionally having the fantasy that what was once so essentially a part of her is still with her. To survive these last two decades has meant placing her feelings in a box and firmly shutting the lid.

Suddenly she feels very tired. She’d intended to walk up to Paddy O’Connell’s white cottage but doesn’t have the strength. Maybe tomorrow, if it’s fine, she’ll climb to the Napoleonic tower and look out across St Fionán’s Bay to the Skelligs. Why do those strange rocks hold such a magnetic allure? She thinks of Mrs Ramsay in that dilapidated house on an island in the Hebrides. Her young son James cutting out pictures from an old Army and Navy catalogue and sticking them in a scrap book. Of their long planned trip out to the lighthouse. How Mrs Ramsay had cherished her time with James, had recoiled at the thought of him growing into adulthood. It was strange that Virginia Woolf, who never had children, should have understood.

But the mist is closing in. She needs to get back. To sit down with a cup of tea and take stock. To assess what she has left.

8

The wind is full of sleet. A night light burns on the sill of her sleeping loft, casting shadows under the eaves. Her dreams are dark and chaotic. Strauss’s ‘Four Last Songs’ drift through her sleep on all-night Lyric FM. She tries not to think of those early hours when Bruno woke with mumps or a nightmare and she climbed into his narrow bed, under the Batman duvet, to comfort him. Or those endless nights when she lay awake beside Brendan’s sleeping back, a sliver of light seeping beneath the curtains from the street lamp below, knowing that the city’s derelicts were huddled in doorways and on park benches, crouched beneath a bush in a local cemetery. Soothed by the barely audible tones of ‘Sailing By’, kept low so as not to wake Brendan, she’d listened to the shipping forecast in the safety of her bed like a member of some secret fraternity of insomniacs, following each point around the coast from Tyne to Dogger, from Fisher to German Bight, on to the Thames and the Bay of Biscay.

Cyclonic 4 or 5, becoming west to northwest 6 to gale 8, perhaps severe gale 9 later. Moderate or rough, occasionally very rough later. Showers, fog patches. Moderate, occasionally very poor.

Then ‘Lillibulero’ and Radio 4 would shut down and switch to the World Service.

She sits up in bed and presses her face to the freezing window. The dark seems infinite, a friend of oblivion. But the disadvantage of sleep is that she must always wake from it, that the curtain edges will event

ually bleed with morning light. She knows that all is not right with her world. She manages by day but at night there’s no escaping that she’s utterly alone. She tries to imagine a life, not even punctuated by the demands of teaching, as retirement looms. She isn’t artistic and has no desire to try her hand at writing a novel or amateur watercolours. She’s been surrounded by good books and art and has no wish to add her indifferent endeavours to the pile.

What, then, can she do? A little charity work? Join the Ramblers, take up bridge? Good God! It all sounds impossibly worthy. At least Brendan hadn’t suffered that gradual seepage and decline. He’d gone into hospital one afternoon, lost consciousness and been dead by the evening. There was no slowing of the intellect, no mewling or puking for him, thank god. He went at the height of his powers. Anyway he was always a hopeless patient, taking to his bed with the slightest snuffle, demanding whiskey with hot lemon and honey, and generally behaving as if he had some terminal illness. How ironic then that when he did, he chose to ignore it. Maybe he knew he was staring death in the face and was too scared to do anything. She feels guilty that she didn’t get him to hospital sooner. But he was adamant that he didn’t want a fuss. She feels a sudden surge of pity and wishes she could hold her frightened husband. Stroke his hair and tell him not to be afraid. But he’d never have coped with a protracted illness. Would have hated the enforced gratitude required of an invalid. The slowing of body and mind. No, if he had to go, then better this way.

It’s no metaphor to say that death is close at hand. It seeps from the pores of the collapsed cottages like mineral salts from rock. It’s there in the fallen stone walls and the wind-blasted crosses lying upturned in the fields she passes when out walking. She’s not the only one to have suffered. She feels close to those women with their broken teeth and calloused hands who had to lift their rain-sodden skirts to piss and shit in a ditch whatever the weather. The walls of their abandoned homes are imprinted with memories: the births of children, the death of a grandfather, the fetid odour of cow dung and peat smoke. For in winter the crofters lived with their animals. And on the hearth, a loaf of soda bread would sit proving in a tin as the dog, its head on its paws, snored, and a clutch of grimy children played knucklebones.

Hearth. How close the word is to heart. A letter away.

Grief requires time but how much? It remains embedded like a virus to be triggered by some small external event. Last night she was woken by the storm and sat watching the lighthouse beam arching across the sky.

A lighthouse. A pharos. A beacon in the darkness warning of rocks to passing ships. Each sweep indicating the passing of another thirty seconds like the pulse on a heart monitor.

Blip, blip. Blip, blip.

The difference between life and death. Grandchildren. She’ll never have any grandchildren. Her genetic imprint stops here.

Tuesday

1

White horses run between the islands as she pegs out her washing. It may be January but after the previous night’s gales it feels almost like spring. It’s the first time it’s been dry enough to hang anything outside. Her knickers and socks snap in the wind. Up on the hill Colm is carrying bales of hay to the cattle. At least she presumes it must be Colm because his red van is parked nearby. It stands out against the brown hillside like a toy truck. She waves but he doesn’t see her. She needs to decide what to do with her day. There are still papers to sort but the weather is too nice to stay indoors. She’s tempted to go to the beach but isn’t ready for that.

She goes back in and cleans up the kitchen, boils the kettle and does the washing up. She rinses the suds off the mugs and pans, leaving them sparkling on the draining board, then washes the bracelet of bubbles from her wrist under the cold tap. Something about the morning sun streaming through her little kitchen window with its blue and white gingham curtains makes her want to leave everything gleaming. She wipes down the table and goes outside to look for something to pick but not much is in bloom. She finds some snowdrops in a ditch and takes them back inside to arrange in a glass on the table.

Up in the bedroom she sorts through the rest of Brendan’s clothes. She can’t believe how many he has. He must have brought things from London over the years and forgotten about them, never throwing anything away. She pulls out a pair of battered walking boots from the bottom of the cupboard, some tartan slippers and a pair of mouldy tennis shoes. There are faded corduroy jackets and shirts with missing buttons. A moth-eaten Aran jumper and assorted woolly hats. As she takes them from the drawers and hangers she’s thrown by his smell. His sudden unexpected resurrection. As she’s sorting everything into piles, deciding what to keep and what to take to the charity shop in Caherciveen, she hears a noise downstairs. But before she can investigate, the bedroom door is flung open.

Martha what are you doing on your hands and knees?

Eugene is standing in the doorway under the low eaves in a wax jacket and mustard cashmere scarf.

I came to see if I can take you to lunch but you look as if you’re otherwise engaged.

Lunch? Oh good morning Eugene, what time is it? I’d no idea it was so late. Now why would you want to take me to lunch? she asks, getting up and smoothing her rumpled hair, conscious that she’s covered in dust and fluff.

Curiosity and an excuse for a chat. I didn’t see much of you the other night. I hope you enjoyed the party. I hate them myself. Don’t tell me you don’t eat lunch. I’m sure you haven’t got anything in. I know the garage shop doesn’t sell much beyond cut-price baked beans and processed cheese like lard.

Well if you insist but you’ll have to wait while I have a shower. I can hardly go like this, she says, catching her reflection in the bedroom mirror. There’s a black smut on her cheek. Give me ten minutes and I’ll be with you.

His Range Rover is parked outside. The dogs curled up in the back behind a grill. As Martha climbs in beside Eugene she wonders, as he speeds down the lanes in a flurry of mud, why on earth she’s agreed to this. They stop at a small quayside inn and he lets the dogs out to stretch their legs. They come bounding out of the boot like bullets from a rifle, running up and down the harbour front barking at the gulls.

That’s it, fellas. Come on now, Brutus, Caesar. Heel, heel. Back with you into the car, come on that’s it, he says, pouring a bottle of mineral water into a plastic dog bowl and placing it in the boot. The dogs jump up obediently, furiously lapping with their spam-like tongues, spraying water all over the rug. Martha wonders whether Eugene has enough learning to know what Brutus did to Caesar.

In the bar they are shown to a table near an inglenook. A peat fire is smouldering in the grate. There are horse brasses and antique fire tongs. All the things that define a pub as having ‘character’. Eugene orders a bottle of Chablis and they sit chatting about nothing much, polite but weary, as the waiter pours the wine and they wait for their grilled hake.

The walls are covered with sepia photographs: huge waves pounding the quay in the storm of ’69, fishermen repairing nets, women in aprons and shawls tied in an X across their breasts as they sit gutting piles of fish beside large wicker baskets like Molly Malone. The place is crowded and Martha wonders who all these people are. What they do. Presumably they’re local solicitors and business men out on expense account lunches. Not long ago the clientele would have consisted of a few glum farmers in flat caps and dung-smeared overalls staring morosely into their Guinness and discussing the outbreak of foot rot or the price of cattle pellets. Pubs like that still exist. No matter what time of day you go in there are always a couple of old fellows sitting by the bar in their Wellingtons over a dark pint. Last time she was in Caherciveen she’d gone into Mick Murts where they sold rope and rat poison at one end of the counter. Guinness and whiskey at the other.

She has no idea why Eugene wants to see her.

It was sudden then, Brendan’s going? he asks.

Yes, she answers. He came back f

rom the shop one Sunday morning after buying the newspapers and complained of pins and needles in his arm. But I couldn’t get him to go to the doctor. You know what he was like, stubborn. Still it was a shock. You never expect it do you? But the doctor told me that even if I’d got him to A&E sooner it probably wouldn’t have made any difference, which makes me feel a bit better. It was a massive heart attack and had probably been waiting to happen for years. Apparently he had a genetic weakness that no one knew about. Thank God it was all over quickly.

Well, I’m sorry Martha. I’ll miss him and there aren’t that many people I can say that about. And I’m sorry for your other troubles too.

She looks away, kneading her bread roll into grey pellets, not wanting to display her discomfort at the commiserations of this man she’s never much liked. His nose is flecked with broken veins and the whites of his eyes have a slight eggy tinge. Outside in the little harbour fishing boats bob on the winter tide. The sky, the sea and the far distant mountains are grey. Why is she here? She should be at the cottage sorting out Brendan’s stuff and getting on with what she came here to do.

This place was special for Brendan, Eugene, she says. That summer you spent with him and Michael as children was important to him too. He was ten wasn’t he? That’s sort of a magical age, don’t you think? Still a child, still innocent but beginning to question the world. …

Why is she talking like this? What does Eugene care? Ten years. Everything can be divided into decades. Three of Brendan. One of Bruno. How many more did she have before her time was up? Two perhaps, three if she’s lucky? Measured like this how short it all is. We spend most of the first half of our lives getting used to it. Learning the ropes, making mistakes and preparing for what lies ahead. And, for a moment, there’s a feeling that it all finally makes sense, that we’ve arrived and understood something about the world. Then, before we know it, it’s all over. The tide coming in and washing away our footprints to leave an unmarked beach.

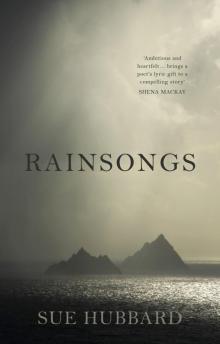

Rainsongs

Rainsongs