- Home

- Sue Hubbard

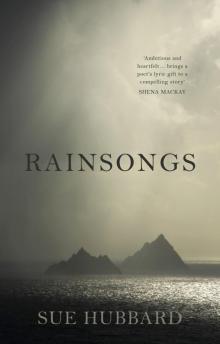

Rainsongs Page 3

Rainsongs Read online

Page 3

It’s not bloody fair, she wailed, a string of snot gathering on her upper lip. Why do you always do this to me?

She’d taken to walking the streets rather than staying at home. Up the Euston Road towards King’s Cross and York Way, past the brownfield sites, the goods yards with their obsolete rolling stock rusting in the sidings, the burger bar and the telephone boxes littered with cards offering Man2Man and Rubber Girl into Water Sports. It made her shudder to think of all those bleak encounters. In the darkening doorways drunks were already bedding down for the night and a thin reek of urine sliced the air. At the back of the station she cut through a run-down estate. Two of the blocks were boarded up where the council planned to redevelop. Discarded needles and used condoms lay in the gutters.

Another day she walked to Soho and Holborn, then down Piccadilly, across Green Park towards Kensington Gardens and watched the ducks and swans on the Serpentine, as a group of Filipino nannies in brown and white striped uniforms pushed their charges round the park in expensive buggies. Then she headed off towards the V&A and the Natural History Museum with its pink and grey striations of brick, like layered sponge cake, and wandered through the vaulted halls, across the wide mosaic floor, past the dinosaur bones, the Brontosaurus and Tyrannosaurus rex. She’d often been there with Bruno, who, like all children, was fascinated by these enormous extinct beasts. It was mid-week and the place nearly empty. With its hushed tones, its high dome and frescoed ceiling it felt like a church. In fact, she read that the architect, Alfred Waterhouse, built it in the style of an Italian Renaissance cathedral. A Victorian museum fit for the glory of God’s creation. She ambled down the long dark corridors, past the mahogany cases crammed with mammals and marsupials, rodents and reptiles, then stopped, for no particular reason, in a gloomy passageway full of stuffed birds with mangy moth-eaten feathers, displayed on twigs and logs. What was it about the 19th century mind that had a passion for killing things only to rearrange them in strange dioramas that were supposed to resemble what they’d destroyed? One case contained nothing but decapitated heads and wings. Tawny owls with huge round eyes. The shiny metallic head of a starling, wings spread to show their full span. A black-backed gull next to a finch’s wing. Further down the narrow gallery was a display cabinet of birds that were extinct, including a dodo from Mauritius with grimy white plumage resembling a feather duster and a billhook beak, like the one in Alice in Wonderland. There were several species of dodo, so the yellowing label said, and most became extinct in the mid-17th century because of their ground-living habits and the damage caused to their eggs and nests by pigs, monkeys and rats released on the island. The Reunion Island dodo was known only from pictorial records and had been reconstructed from these. How, she wondered, could we be sure it had really existed and was not simply a figment of the imagination like the unicorn? Not all just a dream?

After a couple of hours the place began to depress her and she made her way back to the tube, past the Albert Memorial. She’d often seen it from the road, but never close up. There sat Albert on his throne—Victoria’s beloved husband in the middle of all that gilding and mosaic—surrounded by her subjects from the four corners of the globe. A bare-breasted Asia in fringed headdress and half-moon diadem astride a kneeling elephant, escorted by bearded moguls. Europa on a bull with her sceptre and orb. The Americas represented by a maiden with eagles’ feathers threaded through her hair, mounted on a shaggy bison, accompanied by a band of Indian braves. And, finally, Africa, seated on a camel held by a Nubian slave, her hair cut in a heavy fringe like Elizabeth Taylor’s in Cleopatra.

She was erased by grief. She knew she was trapped in the past but was afraid to move on into an unknown future. She’d reached a fulcrum, a point between somewhere and nowhere. Even summoning the energy to get out of bed was an effort. Her life was measured by small achievements. A trip to the bathroom to brush her teeth or wash her dirty hair. Finding clean underwear so she could get out of her pyjamas. She sat at her mother’s little walnut desk staring out of the window watching the man from the council sweep the litter in the street, scooping it up with flat boards, then bagging it into green plastic bags; the illegal immigrants who couldn’t read the signs on the front doors that said ‘no junk mail’ distributing pizza leaflets; the traffic wardens wandering up and down in the rain slapping tickets on illegally-parked cars. The next night she had a dream. In fact she dreamt of nothing. It wasn’t that she didn’t dream. Just that in the dream she was floating in a black void. A tiny particle of isolated matter… That’s what the whole universe was made of, from the highest mountain to a grain of salt.

Just atoms.

Next day she pulled her mack over her old tracksuit and headed towards Clissold Park. It was drizzling, already late afternoon. The lights from the traffic in Green Lanes were blurred. The Turkish shopkeepers covering their pavement displays of newspapers and fruit with plastic sheets. The park was nearly empty as she cut down by the tennis courts, past a man in an anorak with a face like a brick walking his pit bull, the heavy choke chain tightening around the dog’s neck so the veins stood out and spit slavered from its pink chops. She stopped at the Victorian aviary to watch the green and blue parakeets, the pairs of lovebirds on artificial branches billing and cooing, the Chinese pheasant trailing its exotic tail like a muddy ball gown. Next to the aviary stood a clutch of fallow deer sheltering in a pen under a leafless tree. There wasn’t much grass and the rain had turned what there was to mud.

By the library she turned up the path past the small church on the opposite side of the road to the later redbrick Victorian one. The lintel above the heavy wooden door read: 1645. It looked like a village church. Indeed, must have been once when Stoke Newington was a rural retreat out beyond the gates of the city and the reach of the pox and the plague. Sheep must have grazed where the park was. She imagined windmills and potato fields. Green orchards and water meadows where there were now sandpits and swings. It must have been like that when Daniel Defoe lived there. Perhaps he’d walked east up the River Lea, thinking, as he passed the small farmsteads and breweries, tanneries and blacksmith’s yards, of Crusoe and Man Friday. She wandered up Church Street, past the kite shop and the one that restored string instruments, to Abney Cemetery.

Death. She kept being drawn back to death.

William and Bramwell Booth were both buried beneath monumental tombstones at the entrance. She imagined the Salvationists going from pub to pub with their copies of The War Cry, dressed in poke bonnets and peaked caps, banging their tambourines as they preached temperance in foul-smelling snugs in a bid to get East End costermongers and pimps to sign the pledge.

The cemetery smelt of damp moss and leaf mould. A bit of fugitive country that had evaded capture by the city. Brambles and clumps of elder sprouted between Victorian gravestones. Many of the inscriptions were illegible and some of the stones had toppled over as if the earth had moved when the dead tried to push their way out of loamy graves. She wandered down the intricate maze of paths, past the family plots with their ivy-covered mausoleums, to the abandoned church in the middle. The roof had fallen in and iron grilles been erected to keep out squatters and pigeons. What went on there at night? Empty wine bottles and beer cans littered the ground scorched from countless small fires. Why had it been abandoned? Once the well-to-do Anglicans of the parish—women in black satin mourning and jet beads, men in frock coats, a silver watch chain dangling from their waistcoat pockets—must have gathered in the porch to chat with the vicar after the funerals conducted here.

She looks at the clock. 3.30 am. The rain and the endless dark are full of echoes as she lies listening to the wind chasing its tail in the chimney. Finally, as a fragile finger of light creeps across the sill, she falls into an exhausted sleep.

Sunday

1

Paddy O’Connell has been up since 5.30. That’s been his habit for years. Out of bed while it’s still dark, he puts on the kettle, wash

es under his arms and behind his ears. He pulls his work overalls over his long johns and puts on the hand-knitted jersey that his sister Nora made him three Christmases ago. Twice a week and on Sundays he shaves. He hauls in the turf, lights the stove, and folds the clean washing that’s been airing on the wooden rack, before tuning his battered radio to Morning Ireland. He remembers their first wireless. A big old thing it was. The neighbours all came in for a listen. There were two sorts of battery, wet and dry. You had to take the wet battery down to Mickey O’Shea in Caherciveen to get it charged up. With the radio on he doesn’t need other company. He’s happy pottering about his kitchen with its ticking clock and the new calendar that hangs above the stove, next to the framed print of Our Lady that his niece brought back from a school trip to Lourdes. He throws a clod on the fire, pours a mug of strong tea that’s been brewing in the brown pot and sits down at the table. He likes to keep things neat. On the wax cloth the sauce bottles and cruet huddle on the small wicker tray. His folded napkin lies rolled in its wooden ring beside the blue-striped butter dish and matching milk jug.

When he’s finished his second cup he rinses his mug, pulls on his Wellingtons and goes out to fill the cattle feeders on the high ridge and to check for lambs. Many of the ewes look ready to drop. It’s too early, mind, but everything’s out of kilter. He can see it in the storms and high seas, the wild daffodils poking their tips up in the ditches when they have no business to be showing their faces for at least another eight weeks. Things are changing but, he hopes, it will see him out, this life. He’s spent his mornings pretty much the same way for the last thirty years since he was back from Dublin. That was the only time he was away. Mickey Flynn, who was living in Hounslow then, asked him to go to England once for a visit. But he never made it. He fancied seeing Buckingham Palace, the Changing of the Guard, and the Beefeaters at the Tower of London. But, in the end, he hadn’t gone. He’d heard stories of those who’d left West Kerry without a word of English. Who couldn’t read the destinations on the London buses or ask directions from Holyhead. When Jimmy Reen from down the valley went to Australia it had been like a wake. But Paddy had made a bit of money in Dublin working the building sites, though that life never really suited. There were times sitting in some smoke-filled bar down by Parnell Street over a head of the black stuff with the other gangers, when something would remind him of the nutty smell of cattle feed or the view over the headland and his heart would fill fit to bursting. He’d be there in company, wiping the creamy foam from his mouth with the back of his hand and be overwhelmed by a longing to get up and go home. They called him a culchie with his country ways, the city boys. He wasn’t cut out to be a foreman. He didn’t like telling others what to do. He had digs off Cumberland Street where the poorest shopped. Those from the corporation tenements and the traveller encampments. The pavements were littered with second-hand kettles and broken clocks, odd shoes and mismatching china. In Thomas Street he went to the market to buy spuds and cabbage to cook with his bit of bacon, chatted to the stallholders and shoppers but never felt he belonged. So he came back to help his da and then, within six months, his mam had passed away. She was no age. Just fifty-two. It was the cancer. She told no one of her troubles. When they found it, it was very quick. She was gone in a matter of weeks. That was a terrible time. He held things together the best he could but his da lost the will. Then, when his da’s time came, Paddy just carried on doing what he’d always done.

He has more than enough. A car if he needs to get to town and the corn merchant or to meet the lads for a pint and a bit of a blather. The wireless and TV. Most of it, mind, is a waste of the licence money. Though he likes the wildlife programmes. There was a camera crew up here last summer. A couple of young fellows in those tight rubber diving suits that made them look like seals. They were out in a small power boat to film the leatherback turtles that could still sometimes be seen off the coast. They sat on the wall eating their sandwiches and asked if he lived up here alone. One of them had dyed yellow hair on him like a girl’s and an earring, though he was a great big fellow. They couldn’t understand what he did all day. How could he explain there were never enough hours? That he was never lonely up here with his sheep, his few head of cattle and the changing skies. For wasn’t the only time he’d ever felt like he belonged nowhere particular on God’s earth been when he was living in those Dublin digs? He’d worked with good men, drunk with them, but still felt lonely in his bones.

He knew those young divers could never understand the life of bachelors like him who lived alone and worked the land. Tongue-tied and often depressed, many lead solitary lives. That some of them didn’t manage very well, living out of tins, drinking too much and not changing their togs from one week to the next he knew. But he always took a pride.

There was even a girl once, in Dublin. She worked in the café in Crow Street, off Temple Bar where he was after taking his breakfast and always wore the same blue and white checked dress. Her hair was the colour of new dug turf. He felt shy when she bought him his plate of fried rashers and an egg with a yolk as yellow as the sun, which she laid in front of him without a word, on the wax table cloth.

One day he gathered his courage to ask her to go with him along Sandymount Strand on the Sunday after Mass. He got up early to boil the kettle and shave especially carefully, polishing his shoes on a sheet of newspaper and putting on his good suit. The tide was out and there was a smell of seaweed as they stood watching the children flying kites, and dogs running backwards and forwards as if on invisible threads. She had to hold down her coat and skirt against the nosey wind to stop them blowing up over her stocking tops. He bought vanilla ices and they sat under the statue of the Virgin at the far end of the promenade and, even though it was a cool day, the ices ran down the side of the cone onto her Sunday coat, so that he had to dab it clean with his folded handkerchief.

The following week he asked her to a dance. He was a good dancer. Always a willing partner for a turn with one of his sisters. Accompanying them to the dance halls in Caherciveen to keep his da sweet. There were two halls then, both funeral parlours now. Primarily he was a chaperone, hanging round the door so he wouldn’t have to pay the tanner entrance fee, hoping that one of his sisters would remember to bring him out a mineral to quench his thirst. He didn’t mind. He was too shy to walk up to the girls lined up against the wall with their home perms, their hand-knitted cardigans and print dresses, waiting to be picked by a fella. He was happy to loiter outside, cadging the odd fag, sipping his Nash’s Lemon Soda and listening to Jimmy McCarthy’s quartet through the closed door, before ushering his sisters home. His da insisted no later than 11.30. That meant leaving early to push their bikes up the hill. He remembers that May eve when the girls wanted to go into town and the Old Man wouldn’t let them.

Bejesus, why do I have daughters who’re such hoors that they don’t know that the six-penny hops are where girls get into trouble, he shouted, bringing his fist down on the kitchen table. Didn’t they realise that men on the dole lurked outside the dance halls waiting to lure innocent girls into dark alleys where they’d drop their cacks quicker than you could say a Hail Mary. That wheedling tinkers would promise iced sherbets, so that after a few sweet words off would come cardigans, stockings and brassieres and, before they knew it, they’d be fit for nothing but the Magdalene Laundry.

He’d given out something fierce. His sisters had spent the whole afternoon slapping on Pond’s Cold Cream and permanent waving their hair. They cried and pleaded. But the Old Man just put on his cap and marched out to the yard to milk the cows.

It was the only time he’d held her in his arms. He felt her heart beating under her ribs like a trapped bird. Smelt the Vosene in her newly-washed hair, as he manoeuvred her across the dance floor sprinkled with Lux flakes to get up a good shine. The place throbbed with sweat and cheap perfume as they quickstepped to ‘Blackboard of my Heart’ and he worried about stepping on her toes. They drank ging

er beer—for there was none of the hard stuff in the dance halls in those days—and had plates of circular coffee-flavoured biscuits covered in white icing. That Easter he gave her a bunch of primroses and a little palm cross. But she was the youngest. Left at home after all her brothers and sisters had upped sticks. When she wasn’t serving at the café she had to help her mam who had angina. The house was small but someone had to make her daddy’s tea when he came in from working the roads.

They never really said goodbye. One day he just got on a bus and headed back west with his battered suitcase. Years later he heard that soon after he left her mammy had died and she joined the Order of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd. He wonders, if he’d known, if he would have gone back and wed her, fetched her home with him here. He imagines the day she took her final vows, giving up her postulant’s dress for a tunic of heavy black serge, a white linen wimple and a cincture of black leather. After that she’d have been lost to the world. A life of chastity and obedience. Corridors that smelt of silence and beeswax. He can see her slight figure, face-down on the cold stone floor. The Mother Superior covering her with a funeral pall and announcing that her old self was dead. When the cloth was removed she’d have been someone else. Married to Christ.

He hopes that she’s been happy. That she’s had no regrets. It might all have been different. Sometimes he imagines waking beside her in the bed where she’d born all their babbies, the smell of Lux on her. But no, he’s been content enough to watch the clouds and storms sweep in from the Atlantic. To follow the patterns and dictates of the weather. He can organise his days as he pleases around his stock. It’s not a bad life. It’s where he belongs.

Rainsongs

Rainsongs