- Home

- Sue Hubbard

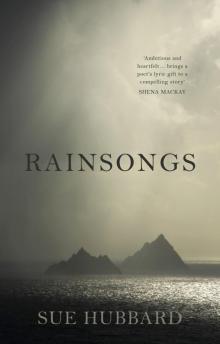

Rainsongs Page 21

Rainsongs Read online

Page 21

The mist has begun to lift and in the distance she can see the jagged outline of the little Skellig. She came out here in drizzling rain but, slowly, it’s cleared to reveal fragile ferns and flowers growing in the crevices. The rock is surprisingly green. There are tussocks of thrift and campion, sea pinks and white alpine flowers. She’d expected it to be more barren. She follows the narrow path up behind one of the beehive shelters, on beyond the large weathered stone cross covered with green lichen, to the chapel. Here, during the long, cold nights the monks gathered to sing the Book of Psalms as they waited for the sun to rise. A symbol both of the Resurrection and the second coming. All through the dark hours, as the world slept and sinned, they kept vigil, observing the offices: nocturns, lauds, terce, sext, none, vespers, compline. During nocturns in the small hours after midnight, they prostrated themselves on the cold, wet stones in the shape of a cross. They believed that at the centre of this cloistered life there was a deep void. That only when the self was finally annihilated would they be created anew in the divine image. Yet despite all the physical and mental hardship, there was no guarantee of spiritual fulfilment. No assurance other than faith and their blind trust in God.

Centuries after the monks came here, the lighthouse keepers followed. Two lighthouses were built in the 19th century. Though the higher one was soon abandoned, having been built too far up for ships to be able to see it in the mist. Some years ago the lower one finally became automatic, removing the need for any permanent residents on the rock. The lighthouse keepers and their families were the last people to live on the Great Skellig. Now puffins and fulmars share its slopes with rabbits. At one time there were up to four families living here and working in shifts. The position of lighthouse keeper was handed down from father to son. Most were Protestants. Few of the names, here began with O’. Thirty children were born on the rock and a teacher sent over from the mainland to educate them. It must have been a harsh life. Storms and endless gales, always wet and cold, vulnerable to the ravages of illness and disease. She walks over to the tiny graveyard. A cluster of wind-blasted headstones stand around a flat slab.

To the memory of Patrick Callaghan who departed this life on 3rd December 1895 aged 2 years and 9 months. Also his beloved brother William who departed this life on 17th March 1899 aged 4 years and 9 months. May they rest in peace.

She imagines losing first one child and then the other to diphtheria or whooping cough. The last time she’d visited Paddy, after he’d come out of hospital, she’d stopped on her way down the mountain and climbed into the high field to explore the small stony area half-hidden in the grass. She’d read that this was a Ceallúnaigh. A children’s burial ground. In medieval times babies and young children had been interred in separate plots, reflecting the Church’s refusal to allow unbaptised infants to be laid to rest in consecrated ground. As she’d stumbled through the bog and reeds, she’d noticed the graves marked by low slabs without any decoration or inscription. In the dead of night, the male members of the family had carried their forlorn little bundles wrapped in sacking, to bury them without ceremony in this lonely sodden spot. The dead child hadn’t been mourned or waked. Though a flowered china bowl or an earthenware dish was placed beside them in the grave. After the burial no one spoke of what had happened as the men trudged silently back up the hill in the moonless rain.

Most lives vanish into oblivion, don’t they? The architect has his buildings, the composer his musical scores. The poet a few slim volumes gathering dust in the furthest reaches of some library. But for most what is there? An album of yellowing photographs. A swimming certificate or a silver cup. A stem of dried lavender caught between the pages of some favourite book. And, if we’re lucky, a small space in someone’s heart. She remembers a wildlife programme on TV. An elephant was mourning the loss of her calf fallen to a poacher’s poison dart. Nothing was left but the skeleton. A mound of bones picked clean by jackals and vultures. The mother elephant circled slowly around and around the remains, running her trunk tenderly across their surface, as if breathing in the last of her offspring.

To live well is to pay attention to each moment. Here. Now. On this windswept needle of rock in the middle of the Atlantic. She listens to the call of the kittiwakes and the pounding waves on the rocks below.

Disappointment is linked to wanting things to be different, isn’t it? Trying to change what can’t be changed. But on this remote rock, high among the clouds, boundaries dissolve. She can feel the world breathing. The tide echoing inside her. In out, in out… Who said: every story has a beginning, a middle and an end, just not necessarily in that order?

Mum, where do the stars go at night?

Nowhere, darling, they’re always there, it’s just that we can’t see them when it’s light.

4

She waits until no one’s around, then unzips her rucksack. Surely the parents of those buried here wouldn’t mind, would understand her need to lay her child to rest with theirs. What better place for Bruno to repose than on this holy island that so caught his imagination, in the company of other children, the puffins and shearwaters?

She places the photo from Brendan’s desk on the flat stone. She’s put it in a plastic envelope, which she weighs down with boulders so it has a fair chance of not being blown away by the wind, and thinks of the Jewish custom of placing stones on a grave as a sign of mourning. Then closing her eyes, she breathes in the salt wind and lets the silence of this wild place sink into her.

There. It’s done. She has kept her promise. Today is the longest day of the year. Slowly she begins the difficult descent back down the steps to the pier and the waiting boat. She is the last to arrive. As she clambers on board the engine splutters into life and the boat pulls out to sea. Then, as she turns to take one last look at the strange rock, the sun breaks through the heavy bank of cloud, painting a silver pathway beneath the old sky.

I have relied on the voices of those born and bred in Ireland to express opinions about their own country and am grateful to the following sources:

Magnum Ireland, Brigitte Lardinois and Val Williams (editors), Thames & Hudson, 2005.

The Life of Riley, Anthony Cronin, Alfred A. Knopf, 1964.

Dead as Doornails, Anthony Cronin, Caldar and Boyars, 1976.

Tides of Change: Memories of a Kerry Childhood, John Curran, Curran Publishing, 2004.

Voices of Kerry—Conversations with Men and Women of Kerry, Jimmy Woulfe, Blackwater Press, 1994.

Puck Fair: History and Traditions, Michael Houlihan, Treaty Press, 1999.

Celtic Music: Third Ear—The Essential Listening Companion, Kenny Mathieson (ed.), Backbeat Books, 2001.

Lifetimes—Folklore from Kerry, Doghouse Books, 2007.

‘Irishness is for other people’, Terry Eagleton, London Review of Books, Vol. 34, No. 14, 19 July, 2012.

Sun Dancing: A Medieval Vision, Geoffrey Moorhouse, Phoenix, 1998.

The Laugh of Lost Men: An Irish Journey, Brian Lalor, Mainstream Publishing, 1997.

Why Not? Building a Better Ireland, Joe Mulholland (ed.), Joe Mulholland, 2003.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Linda Rose Parkes, Jules Smith, Marianne Lewin, Judy Annan and Annie Wilson for their advice and suggestions. To Chris and Sarah Dyson for making available their lovely Suffolk cottage to work on the final draft and to Noelle Campbell Sharpe for inviting me on a number of residencies in Cill Rialaig, Kerry, which provided the background.

The lines of Colm’s poem are from my poem: ‘The Idea of Islands’ from The Forgetting and Remembering of Air (Salt, 2013)

Any resemblance to people living or dead is mere coincidence. Only the place is real.

First published in 2018 by Duckworth Overlook

LONDON

30 Calvin Street, London E1 6NW

T: 020 7490 7300

E: [email protected]

/> www.ducknet.co.uk

For bulk and special sales please contact [email protected]

© 2018 Sue Hubbard

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, hired out, resold or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publisher.

The right of Sue Hubbard to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.

Typeset by Danny Lyle

[email protected]

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

ISBN 978-0-7156-5285-5

eISBN 978-0-7156-5287-9

Rainsongs

Rainsongs